Brief reflections on Saint Agnes' day

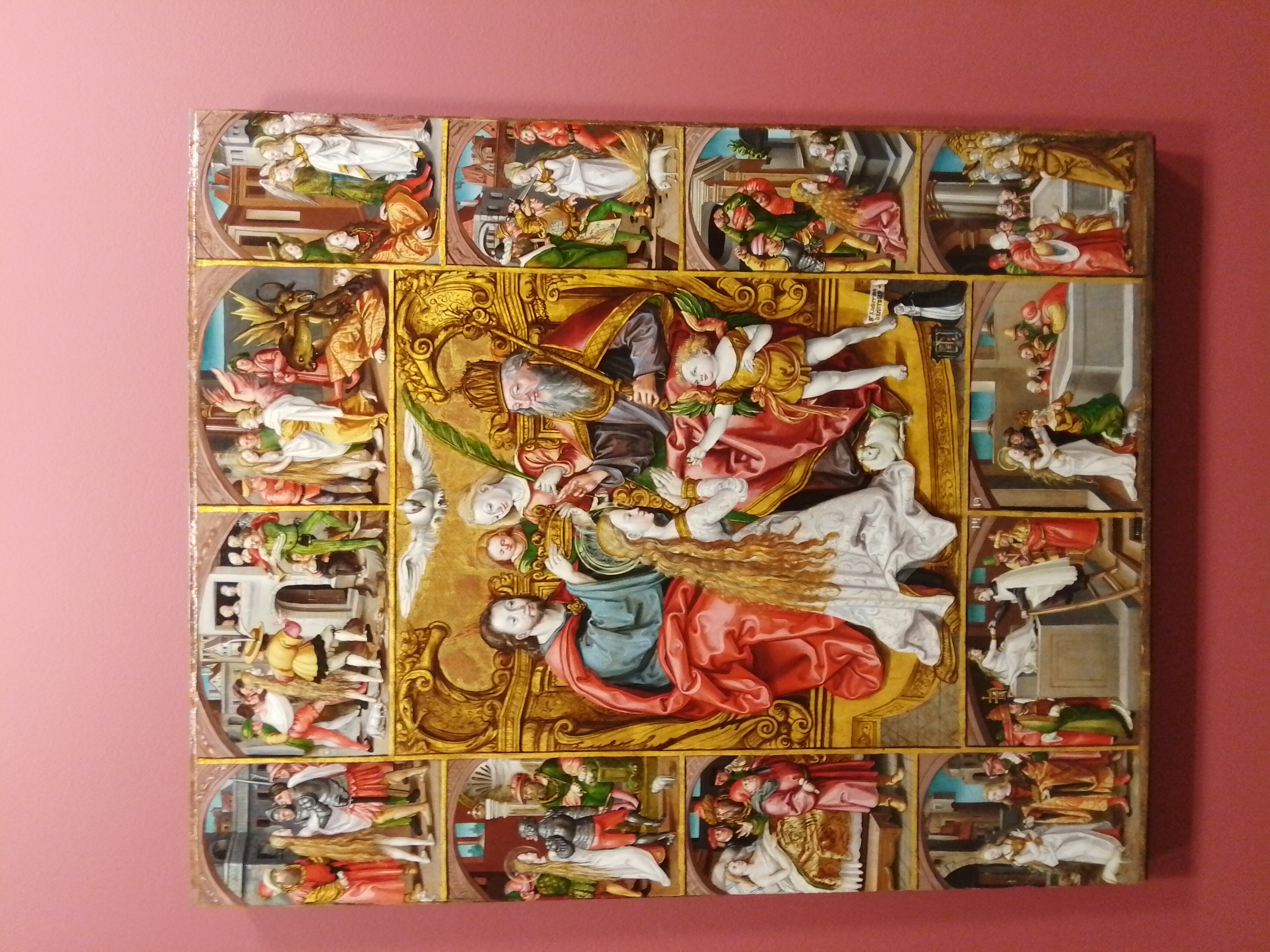

By coincidence — but some say there are no coincidences — I’ve just found out that today is the feast of Saint Agnes. I wasn’t familiar with her story, but when I was in France, last December, I saw a medieval painting in a museum in Montpellier that called my attention. It was an anonymous painting telling the story of her martyrdom, with different scenes of her life displayed almost in the form of a comic book.

Agnes was a young woman from a rich Roman family who converted to Christianity. According to the legend, when she was 12 or 13, a spurned suitor denounced her for being a Christian, therefore, as a punishment, she was paraded nude on the streets in order to be taken to a brothel (but her hair miraculously grew to cover her, and anyone who tried to have sex with her was struck blind). Then they tried to burn her (but the fire would not catch). So they stabbed her in the throat, and she died. She has since become the patron saint of virgins. Her skull has been preserved and it can be seen displayed in the Sant’Agnese church, in Rome.

There is also a famous poem by John Keats called “The Eve of Saint Agnes“, which is inspired by the old folk belief that young maidens could see their future husband in a dream if, on the eve of Saint Agnes — that is on the night before the feast — they performed certain rituals. These could include fasting and transferring pins from a cushion to their sleeves while reciting the Lord’s Prayer, although different accounts give different rituals. Ben Jonson, one of Shakespeare’s most famous colleagues, mentions the custom in a text from 1603. John Aubrey, who seems to have been Keats’ main source, describes it in more detail in his “Miscellanies” (1696).

In Keats’ poem, the ritual is described as the young maiden going to bed without supper and then lying nude under the covers, with her head resting on a pillow and her face turned up to Heaven as she sleeps.

They told her how, upon St. Agnes’ Eve,

Young virgins might have visions of delight,

And soft adorings from their loves receive

Upon the honey’d middle of the night,

If ceremonies due they did aright;

As, supperless to bed they must retire,

And couch supine their beauties, lily white;

Nor look behind, nor sideways, but require

Of Heaven with upward eyes for all that they desire.

The idea of the maiden’s future husband appearing in a dream is interesting. Jorge Luis Borges said once (apparently referring to some quote by T. S. Eliot that I could not find), that “In the Middle Ages, when people believed in the divine origin of dreams, it made them dream better dreams”. It’s a witty saying, but I think it’s also true. Freud and psychoanalysis first demoted dreams to a mere result of sexual repression, and, for modern science, dreams are just sequences of random imagery from our brains with no ulterior meaning. Therefore, we do not have the same interest in dreams that ancient people had, and, as a result, not just our interpretation of dreams, but our dreams themselves, have become poorer.

And of course, all those curious folk rituals, not to mention the celebration of the feasts of most saints, have almost disappeared in an increasingly secular Europe, which is, in many ways, sad too. We no longer believe in saints, witches, demons or dreams — but we do believe in “global warming”, “aliens”, “fact checkers” and “gender fluidity”, so there’s that…

The legend of St Agnes has resonance w/ the later one of Lady Godiva. Both went naked in public view but were initially protected by their long hair and additionally by God striking the voyeurs blind. Agnes was under persecution by a pagan emperor and martyred by his licentious minions. A millennium later Godiva took a much more active role in her shameful ordeal at the hands of secular authorities, but being under God’s protection because of her righteous mission remained unscathed and w/ her reputation intact. Peeping Tom, the perverted tailor, not so lucky.

The idea of a dream from heaven, which Keats recalls, has been embedded in the Left’s worship of secular saint MLK. He had a Dream. And all good lefties are encouraged to have a little, ambitious personal dream, but to partake in the larger secular dream: a revolutionary dream – to crush White supremacy and establish a world of equality – the Marxist dream. Imagine there’s no heaven, but become a dreamer.